Butterflies and Signs

“Do you remember the blue butterfly?” he asks, his voice slow and sleepy. My youngest child is draped across the small couch positioned at the foot of my bed, trying his best to delay the inevitable slumber. It’s late enough that I should ignore this question and urge him toward rest, but the butterfly…the butterfly is worth these few extra minutes, so I concede.

“In Costa Rica?” I reply.

“Yea. I fink it was on the last day when we goed back home,” he says, his five-year-old memory surprisingly precise.

“Yes, it was. What about that butterfly?” I ask.

“I fought we were gonna runned it over wif the car,” he says, eyebrows at attention.

“No, silly boy. We weren’t gonna run it over. That was our guardian angel.” I smile.

“It’s just a butterfly, Mama,” he giggles.

“Maybe. But Mama’s pretty sure it was meant for us.”

We typically spend our August awash in the final weeks of Midwestern heat. But this year, instead of baking in the Michigan sun, we spent part of our August in the hot blaze of Central America as we explored the beaches and mountains of Costa Rica. This dream had lived within me forever, but with my 40th birthday around the corner and the weight of five years of foster parenting on my back, I was eager to escape and experience a different way to live out the evaporating summer.

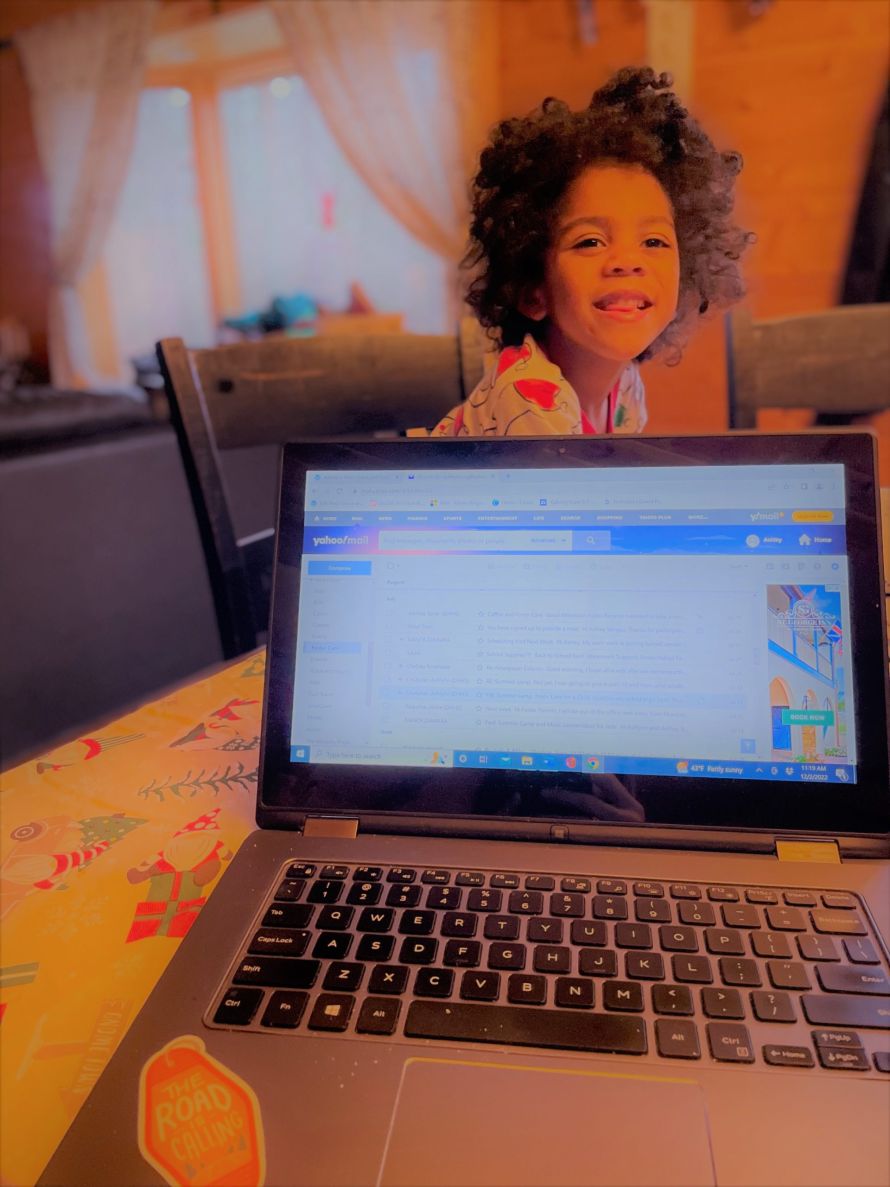

Fully adept at the American road trip, I am rarely phased by travel with children. We have ventured near and far with our gang of ruffians, but we had never attempted to buckle these boys onto a plane and out of the country. With the exception of Canada, international travel was not something we’d done with any of our children, let alone all of them at once. I would not be deterred, though, and in early winter when the sun was nowhere to be found, I cracked my dust-covered guide to Costa Rica and started booking beachside huts and lodges tucked deep in the rainforest.

Before I knew it, I’d plotted out a 12-day itinerary and reserved the only 4WD rental car I could find that would accommodate all 6 of us. Then, I filed that dream away until the end of July when I pulled it back out and found that my brazen January confidence had left me. I sat on the floor of my closet, packing and repacking the same four carry-ons, wondering what I had done.